A Chorus Line was one of the biggest musical hits Broadway had and has ever seen. It was a backstage musical about Broadway’s gypsies, the dancers who work and battle so hard to win a part in a show on The Great White Way. This very different idea for a musical seemed to come out of nowhere.

When it closed on April 28, 1990, it established the new long-run record on Broadway – 6,137 performances. It ran for close to 15 years and A Chorus Line always seemed to be sold out.

In 1976, it won nine Tonys, including Best Musical, and five Drama Desk Awards, including Outstanding Musical. It also won the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. In 1984, the show received a Special Tony Award for becoming Broadway’s longest-running musical.

Humble Beginnings

A Chorus Line did not start out to be a Broadway show. Two dancers, Michon Peacock and Tony Stevens, hosted workshop sessions with other dancers. The first session was held at the Nickolaus Exercise Center on January 26, 1974. Each of the workshop sessions, which were taped, featured dancers telling their stories. The idea was to create a professional company that could develop possible workshop performances for dancers that focused on their lives as gypsies.

In Walks Michael Bennett

Michael Bennett, dancer, director, and choreographer, was invited to one of these meetings. He was supposed to be an observer. But Bennett apparently saw something in the stories he heard, and he quickly took over the sessions.

Michael Bennett, dancer, director, and choreographer, was invited to one of these meetings. He was supposed to be an observer. But Bennett apparently saw something in the stories he heard, and he quickly took over the sessions.

Exactly what happened between the time Bennett arrived and A Chorus Line became a musical is up for debate. Later, Bennett claimed that she show was entirely his idea, however, there were numerous lawsuits that claimed the contrary. What did happen within the process that created A Chorus Line is certain dancer’s stories became the foundation text for the show.

The Musical

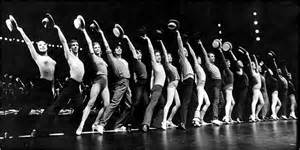

A Chorus Line focuses on a dance audition where performers are vying for a spot in a Broadway production. It reveals the dehumanizing aspect of Broadway auditions, while, also, highlighting how individualized and unique each person who’s auditioning is. The premise of the show demands that those auditioning share something from their personal life, that is, be truthful, with the director/choreographer casting the show. He wants to cast people who are real, vulnerable, and tough.

In the original preview performances, as the piece was being developed, different dancers would be selected at the end of the show to be cast members. But audiences seemed dissatisfied when the character of Cassie, who was clearly superior to all others and had a stellar audition, did not get cast. Eventually that was changed and Cassie was always selected to be in the cast at the end of the show.

Joe Papp Believes

Broadway hits are often a result of a confluence of personalities and forces that come together in the right place and at the right time. Thus, for Michael Bennett and the others involved in A Chorus Line, it was fortuitous that Joseph Papp, who ran the Public Theatre, was interested in being involved in the development of innovative work.

Papp’s company did not have enough money to mount the show. They borrowed $1.6 million, a huge gamble, and opened Off-Broadway at the Public on April 15, 1975. The run sold out instantly and the Broadway transfer was planned. A Chorus Line opened on Broadway on July 25, 1975. It was impossible to get a ticket.

Hamlisch, Kleban, Kirkwood and Dante

Certainly much of A Chorus Line’s success can be attributed to those who created the music, lyrics, and book. One of the things that makes this musical so effective is the manner in which it dynamically utilizes all three elements.

Marvin Hamlisch created the music and Edward Kleban the lyrics. Hamlisch was a noted composer and pianist who had already won numerous Grammies and Oscars for his film work on various movies, including The Sting and The Way We Were. Kleban was a composer and lyricist who’s biggest hit and most famous work would be A Chorus Line.

The book writers were James Kirkwood and Nicholas Dante. Kirkwood, who was an actor and writer, would never have another hit as big as this musical. Dante was a dancer and writer who Bennett asked to be a part of the process. In A Chorus Line the story of Paul, the homosexual Puerto Rican dancer who started performed in drags shows at the start of his career, is based on Dante.

It is definitely the music of Marvin Hamlisch that gives the musical A Chorus Line so much of its power and dynamics. When combined with the other elements, which were finely honed and tuned through Bennett’s eye, and funneled through the stellar direction and choreography of Bennett, the musical became a massive hit.

A Sensation Singularly

A Sensation Singularly

A Chorus Line was a magnificent show that simply enthralled audiences. The honestly acted stories, dynamic dance numbers, savvy lyrics, and complex score that featured amazingly catchy and memorable tunes epitomized what made Broadway musicals great. The show was featured in New York’s I Love NY campaign for years, and for more than a decade it was the most sought-after ticket on Broadway.

In the End

A Chorus Line seemed to run forever. However, many of those who created it did not outlive its run. Michael Bennett died of complications from AIDs on July 2, 1987 in Tucson, Arizona. He was 44. Kleban died at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York of complications from throat cancer. He passed on December 28, 1987 at the age of 48. Kirkwood died in his Manhattan apartment of spinal cancer in 1989 at the age of 64. Nicholas Dante passed away due to AIDs complications in New York on May 21, 1991, a year within the closing of the show. He was 49 years old.

Hamlisch continued to prosper and thrive. After a storied career that included creating music for various popular Broadway shows and films, writing hit songs for some of the 20th century’s major recording artists, and appearing on numerous TV shows and specials, Hamlisch died in 2012 at the age of 68 in Los Angeles California.

A Chorus Line, which also changed the way in which Broadway does business, is the legacy of these creative artists as well as the numerous performers whose stories were told in the musical and producer Joseph Papp.