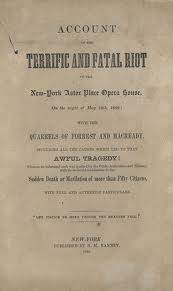

The Astor Place Riot, which occurred on May 10, 1849, was at that time the deadliest event of its kind in New York City. The riot took place outside the Astor Opera House and it was partly the result of a rivalry between American Shakespearean actor and tragedian Edwin Forrest and his English counterpart William Charles Macready. The riot was in essence a three-sided affair.

At first it was a battle between immigrants and U.S. citizens who had lived in the country for numerous generations. It then became a fight between the state militia, which was controlled by those with power and money (the upper class) and the two groups that had been at odds with each other, immigrants and nativists. It became a class war.

Forrest and Macready

American actor Edwin Forrest was widely respected in the U.S. The first time he ventured to England to act Shakespeare, he proved to be very popular. When British actor William Charles Macready toured the U.S. the first time, he too met with great success. On Macready’s second tour, Forrest followed him throughout the country performing the same Shakespearean roles in the same cities as his British rival. The dueling tours received a lot of press coverage with most critics and journalists endorsing the homegrown talent, Forrest, as being superior.

When Forrest went on his second tour of Britain the crowds were thinner, the critics less supportive, and he was simply less popular. The American actor blamed Macready for his misfortune and one night attended a performance by Macready of Hamlet. Forrest hissed and jeered the British actor loudly causing Macready to later claim that the American had no taste.

The growing resentment between the two actors and the public and journalistic battles that they engendered helped set the stage for the Astor Place Riot, which occurred during Macready’s third and final U.S. tour.

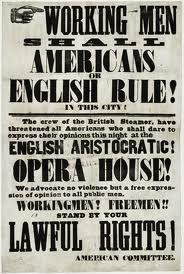

Culture Wars: U.S. Versus England

The U.S. had long stood in England’s shadow as far as art, theatre and literature were concerned. Early theatre companies in America were composed of British actors and most of the plays they performed were either penned by British playwrights or were imitations of British works. Forrest was the first great homegrown tragic actor to tread the boards in the U.S. Plus, he had encouraged American playwrights to create dramas focusing on themes and subjects important and indigenous to the country. The actor sponsored a playwriting contest for U.S. writers in which they created dramas focusing on a Native American theme. The play that won that contest, Metamora or the Last of the Wampanoags written by John Augustus Stone in 1829, became a permanent part of Forrest’s repertoire and was celebrated and burlesqued on American stages.

For quite some time, U.S. playwrights had focused their efforts on defining what made Americans better than their British counterparts and on themes and subjects important to the country. Additionally, American actors were attempting to gain respect in England by proving that they could indeed interpret Shakespeare as well as if not better than those native to the island nation of the great bard. In the 19th century, Shakespeare was the proving ground for serious English-speaking actors on both sides of the Atlantic.

For the most part, the English looked down on the U.S., observing that American’s were uncouth, unschooled and ill-mannered. In their eyes, our lack of decorum was equal to barbarianism and we were at best second rate when it came to serious acting, literature and art.

Prior to the Riot

When Macready arrived in the U.S. for his farewell tour the man who was considered by most to be the greatest English actor of his generation was locked in a cultural war with Forrest, America’s first great actor. Adding fuel to an already hot fire was the fact that Forrest was a man of the people. In his early years, he had performed at New York’s Bowery Theatre. The Bowery Theatre, which attracted audiences from the city’s lower class Five Points neighborhood, was known as “the slaughterhouse” due to the fact that much of its repertoire was composed of violent melodramas. Macready was seen by Americans as being a member of the upper class; in other words, those people against whom we had rebelled. He was the antithesis of Forrest.

Macready was booked to perform Macbeth at the Astor Place Opera House, which was seen as being an upper class venue. At the same time, Forrest was in the same play at the expansive Broadway Theatre just a few blocks away. Supporters of Forrest had bought a large number of seats for Macready’s performance. They were determined to interrupt and denounce the British actor. The intention of these Forrest supporters was no secret so on the night of the event those who were for Macready, immigrants, showed up to offer their support.

The confluence of these two forces would prove to have a disastrous result a few days later.

Three Days Earlier

Three days prior to the riot the hundreds of Forrest supporters who had bought tickets to the performance took their seats in the balcony of the opera house. From there they shouted down Macready and threw rotten eggs and vegetables at the stage. Unable to properly finish his performance, the great British actor eventually withdrew from the stage and announced that he would leave for England on the next ship.

However, many of the cultural and financially elite of New York petitioned the British actor to stay and perform. He agreed and was next scheduled to act at the theatre on May 10, 1849.

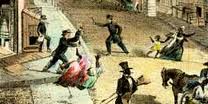

The Astor Place Riot

The evening of the riot thousands of supporters of Forrest and Macready gathered outside the theatre. Tempers and passions were hot. Estimates had the crowd at 10,000 when the performance started that evening at 7:30.

There were 150 police inside the theatre and 100 outside of it. Early in the day, New York mayor Caleb S. Woodhull was informed by police chief George Washington Matsell that he did not have enough police to handle the situation. The mayor called out the state militia, which included horsemen and light artillery. A total of 350 men were brought in to support the police. This was the first time a state militia had been called out to quell a crowd.

Macready’s performance played out pretty much the same way it had three nights before. He was unable to finish the played and played it out in dumb show. The actor slipped away from the theatre in disguise.

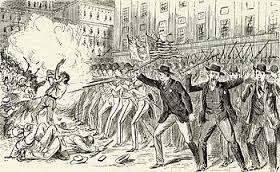

Officials, who were afraid they were losing control of the crowd, called the militia to the scene at 9:15. They were pushed, threatened and physically attacked. Many of the state militia were injured. They warned the crowd to disperse but could not be heard. After firing into the air, they unleashed salvos into the crowd, sometimes at pointblank range. People fell to the crowd injured and dead. Those killed were primarily working class people and many were innocent bystanders.

Results and Consequences

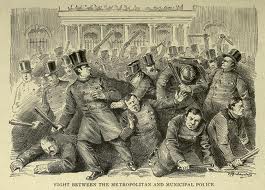

The next day, May 11, saw thousands attend a meeting a City Hall Park where they talked about avenging those who had been injured or killed. That same day mothers, wives and other relatives went to nearby bars and the morgue to try to find their loved ones that had been killed. Although thousands started up Broadway towards Astor Place, they were dispersed by authorities, perhaps averting another day of carnage.

It was estimated that from 22 to 31 rioters were killed on May 10 and 48 were wounded. From 50 to 70 policemen were injured and 141 members of the state militia were hurt. It was the deadliest event of its kind in the country. Those in power praised the work of the police and militia while the working class denounced what had occurred. The Astor Opera House became known as the Massacre Opera House and the DisAster Place.

Eventually, the Astor Opera House was closed down and it became the New York Mercantile Library. Further uptown, away from the Bowery, the Academy of Music was built to house opera and other events. That would be the same Academy of Music that years later would burn down leaving a French ballet troupe without a performance venue. That ballet company would become a part of the show The Black Crook, helping to turn what probably would have been a flop into Broadway’s first long run show.