Egbert Austin “Bert” Williams (November 12, 1874- March 4, 1922) was a black performer unlike any other of his generation. He took the stereotypical black character, which had roots in T.D. Rice’s 1830’s Jim Crow creation, and while playing comedy managed to create a pathos that was born from the racial bigotry, prejudice and inequalities that blacks faced in America. Williams’ characters were not based on racial stereotypes and his comedy never focused on debasing blacks. This was a major contrast to how other performers, both white and black, interpreted black roles.

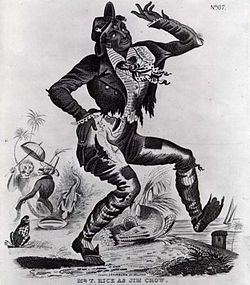

Jim Crow

Thomas Dartmouth “T.D.” Rice, who was born in the lower East Side of New York, is credited with creating the Jim Crow character, which became popular in minstrel and variety shows. Rice’s “Jump Jim Crow” number, in which he sang, danced and mimicked black behavior and speech, was a huge hit and helped instill black racial stereotypes for more than a century. Like others of the time, Rice would blacken his face and other exposed areas to create the illusion that he was a black man.

Blackface in America

In the 19th century in the U.S., the image of blacks on stage was created by whites who “corked up” (burned cork and then applied it to their skin) in order to mimic an entire. The corking up, which was also known as blacking up, resulted in black characters whose skin was darker than night. Also, eyes, lips and the palms of one’s hands would be enhanced with white, which created a cartoon-like contrast between the two colors and allowed performers to utilize big eye movements, protruding, thickened lips and hand motions that were magnified.

This was done by whites portraying blacks and it was also copied by blacks creating black characters. Thus, Bert Williams, who was born in Nassau, Bahamas, and was fairly light skinned, blacked up to meet audience expectations of what a black looked like.

Williams in Variety and Vaudeville

Bert Williams first got noticed when he teamed up with variety performer George Walker. Williams & Walker became a major hit in variety. Their act was different than others of the time and what they did in these early years would define Williams as a performer throughout his career.

In an effort to distinguish themselves from white performers pretending to be black, the duo billed themselves as “Two Real Coons” (the Coon Song was an accepted genre of the time). The manner in which they performed standard black songs was unique in that they were often seen as mocking white performers conceptions and interpretations of blacks. As black performers they satirized whites. When they did new material, and this is especially true of Williams, it was done in a manner that connected with audiences on a universal level without any regard to their race.

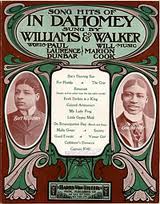

They appeared in two important hit shows, Sons of Ham (1901) and In Dahomey (1903). Sons of Ham was a musical farce that was unusual in that it rejected stereotypical black roles. It was during Sons of Ham that Williams performance persona would focus on portraying a man who was down and out. In 1901, he recorded “When It’s All Going Out and Nothing Coming In” and it became one of his biggest hits.

In Dahomey offered New York something it had never before seen- the first full-length black musical on Broadway. The musical comedy saw a 53-performance run, which at that time meant it a huge success on Broadway. It went on a tour of England and gave a command performance at Buckingham Palace. While on tour, Williams and Walker were initiated into the Edinburgh Lodge of the Freemasons. This was ironic in that the Scottish Masons did not racially discriminate but U.S. chapters did, including those in the northern states.

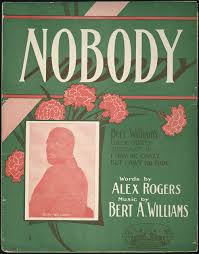

Nobody

In February 1906, the musical Abyssinia opened at the Majestic Theatre and Williams and Walker scored another big success, Williams, who co-wrote the score, would find his signature number in the show, “Nobody.”

Williams wrote the music to Nobody and recorded the number.

The song recounts the struggles of a man who finds that when all is said and done he’s simply alone on this earth with his misery. It is wry, witty, sad and funny. Partly spoken and partly sung, Williams’ rendition of “Nobody” is ironic and painfully truthful.

The lyrics read in part:

When life seems full of clouds and rain,

And I am filled with naught but pain,

Who soothes my thumping, bumping brain?

[pause] Nobody.

When winter comes with snow and sleet,

And me with hunger and cold feet,

Who says, “Here’s two bits, go and eat”?

[pause] Nobody.

I ain’t never done nothin’ to Nobody.

I ain’t never got nothin’ from Nobody, no time.

And, until I get somethin’ from somebody sometime,

I don’t intend to do nothin’ for Nobody, no time.

Ziegfeld Follies

In 1909, Williams & Walker broke up. Walker, who was suffering from syphilis, was too ill to perform. 1910, Florence Ziegfeld signed Bert Williams to appear in his Follies. At that time, it was unacceptable for blacks and whites to appear on the same stage together. Many of the white performers protested the signing of Williams and said they would not appear on the same bill with him.

When Ziegfeld heard this he replied, “I can replace every one of you, except [Williams].” Williams at first got the cold shoulder from many of the performers and the writers took their time creating material for him. When the show opened in June Williams was a hit. One hugely successful skit focused on boxing and used as its inspiration the racially-charged “Great White Hope” heavyweight bout that had just taken place between Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries. It was during his run with the Follies that his poker pantomime skit became popular. It was immortalized in the 1916 movie A Natural Born Gambler.

Williams in A Natural Born Gambler.

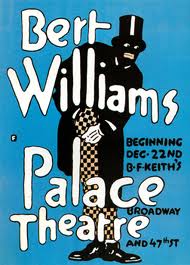

He went on to have a great run with the Follies, ending his association in 1919 due to what he felt was poor material. Just prior to leaving Ziegfeld, Williams had another first becoming the first black performer to top the bill at New York’s prestigious Palace Theatre.

Groundbreaking Performer

Bert Williams career was cut short when he fell ill and collapsed on stage in Detroit, Michigan, with pneumonia. He was performing in the musical Under the Bamboo Tree. At first when he collapsed during the show, the audience thought it was a comic bit. It’s reported that Williams said, “That’s a nice way to die. They was laughing when I made my last exit.”

It was his last exit. He travelled back to New York to recover but never did. The man who master comedian W.C. Fields called “the funniest man I ever saw and the saddest” died on March 4, 1922 at the age of 47.

To say that Williams was an amazing talent is stating the obvious. That alone gave him a career in the theatre. Perhaps more important was the fact that through his ability to uniquely interpret the portrayal of blacks on stage by whites and his talent for creating a black persona that was defined by contrasting emotions, nuance and depth, Williams offered food for thought for audiences of all colors.